Cattle feed on land owned by Jim English in

Alva. The land is adjacent to Babcock Ranch. English believes developing

the Babcock land will cause more flooding on his land, which already

floods in the wet season.

Newspress.Com

Babcock Ranch plans stir

water fears

Developer vows town will have 'no impact'

http://www.news-press.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20070624/BABCOCK/706240398

Jim English expects his Alva farm to flood during

the next couple of months. It's the rainy season.

But what will happen, he wonders, if a West Palm Beach developer builds a new

town just north of him that exceeds today's state water runoff limit by 45

percent?

"Flooding damages our pasture and our citrus grove, and that reduces our

income," English said, not elaborating on the financial impact.

"People need to understand that we've got a problem."

|

|

"We noticed that the figures ... seemed to

be higher than the ones allowed in our (water) discharge rate map," said

Ricardo Valera, a division director with the water management district, which

oversees these kinds of water issues in Southwest Florida.

This is the first of two permits Kitson & Partners must acquire from the

district, with more permits needed from governing agencies such as the U.S. Army

Corps of Engineers, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and

Charlotte County.

Syd Kitson, chairman of the company, promotes his development as a hybrid — a

self-sustaining town where people and the environment co-exist.

"We're talking it through right

now," he said of the permit. "We're

going to do everything we can so things work out for everybody."

The 800-acre English farm, where cattle is raised and citrus grown, has been in

the same family for nearly 130 years.

"My grandfather came there by ox cart in 1878, from southern Georgia. It

took him six weeks," English said. "I'm the fourth generation in my

family that that piece of land has provided an income to."

|

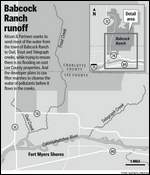

The biggest neighboring development in the works is Kitson's, planned on 17,000 acres that straddle the boundaries of northeast Lee and southeast Charlotte counties. Kitson is focusing on the 13,000-plus acres in Charlotte for now, because he has not yet gotten approval to create a special district in Lee that would generate money for roads and sewers.

The Charlotte piece will discharge water at a

rate of 39 cubic feet per second per square mile, potentially enough to cause

some flooding, the water management district report shows.

That rate of water release is allowed in Lee, but in Charlotte, the water

management district restricts water releases to 26.9 cubic feet per second per

square mile.

That means Kitson & Partners is surpassing the district's water discharge

limit by 45 percent.

"The secret to the success of the design is

water that leaves the site has to be held back, and they have to treat it and

release it slowly," Valera said. "It won't get worse. That's part of

the review process."

English, an Alva resident all his life, has been proactive.

Not only is he following every step of the water

management district process, he has hired his own consultant.

Tommy Perry, an engineer with Johnson-Prewitt & Associates Inc. in

Clewiston, believes Kitson's proposal needs work. How does Kitson plan to keep

water from Cypress Creek, notorious for overflowing and flooding parts of Alva,

including English's farm? How does Kitson plan to direct the water toward Owl,

Trout and Telegraph creeks instead?

"Their plan doesn't fully address the problem as it is right now,"

Perry said. "They are legitimate questions."

Kitson believes he can answer them. If there is

too much discharge, regardless of what is and is not allowed, he wants to

address that.

"There should be no impact," he said. The water "is going to run

off at a rate that does not impact those people (in east Lee County). Period.

There is no other alternative."

That leaves one more major water issue to

address: the Caloosahatchee River.

The water management district's limit of 26.9 cubic feet per second per square

mile applies to runoff flowing into the river too.

Ruby Daniels, president of the grass roots civic group ALVA Inc., was concerned

from the beginning, when Kitson & Partners bought Babcock and planned to

develop part of it.

"ALVA Inc. is trying to preserve the natural

beauty of the area and that's a huge challenge when people are trying to develop

large tracts of land," she said.

Runoff heads south and eventually ends up in the Caloosahatchee, which flows to

the Gulf of Mexico, one of the gems of Lee County's $2 billion tourism and

hospitality industry. Dirty water that flows to the Gulf can bring algae to

Lee's beaches, clouding the water and creating a horrible smell.

The Babcock water will be treated, Kitson said,

in the filter marshes along the southern edge of his town.

"That water is going to be cleaner," he said.

English is keeping an open mind, and he will be watching.

"I'll have to see what the plan is" when it's done, he said.